What is Yin Yoga and why should we practice it?

words by Kerryelle Bucknell

What is Yin Yoga – why would someone want to practice it?

Yin yoga is a deeply meditative style of yoga where rather than target the musculature of the body like a flow practice does, we are targeting the fascia system in the body. Incorporating ancient wisdom from the Traditional Chinese Medicine traditions, we also target the flow of qi or chi (prana or energy) in the body via highways called meridians that relate to organs systems in the body. The synergy of the two produces the modern yin practice.

What is fascia?

Fascia is a connective tissue primarily made up of collagen with elastic fibres that attach, cover, stabilise and enclose all muscles and organs. To give you a visual example, you could think of the white pith that you find enclosing an orange or mandarin, both as a whole enclosing the entire shape, and around and through each of the individual segments as being similar in structure to your fascia. The third element to fascia is a ground substance which in healthy fascia is gelatinous and fluid in texture and this fluidity allows muscles and organs to glide smoothly over each other without resistance and friction. Healthy, happy fascia is fluid, springy and strong and allows the body to rebound energy through movement with a light quality. This provides efficiency in our movements, greater flexibility and space.

Fascia is arranged in ‘trains’ in the body and over time and as a result of an increasingly sedentary lifestyle, these chains can become dense and fibrous and can be a major contributor to a lack of flexibility in the body not only in muscles but also by restricting joint movements.

The fascial system also affects our tendons, ligaments and joints which work together to provide mobility to our limbs. Ligaments connect our bones to other bones and tendons connect our muscles to bone. These types of connective tissue have a much slower rate of blood flow and our yin practice of slowly stretching our fascia provides them with nourishing and lubricating moisture which allows them to relax and release using the time and the space provided in the shapes. Connective tissues respond to a slow and steady load vs our muscles which like to be contracted.

What is a qi and what is a meridian?

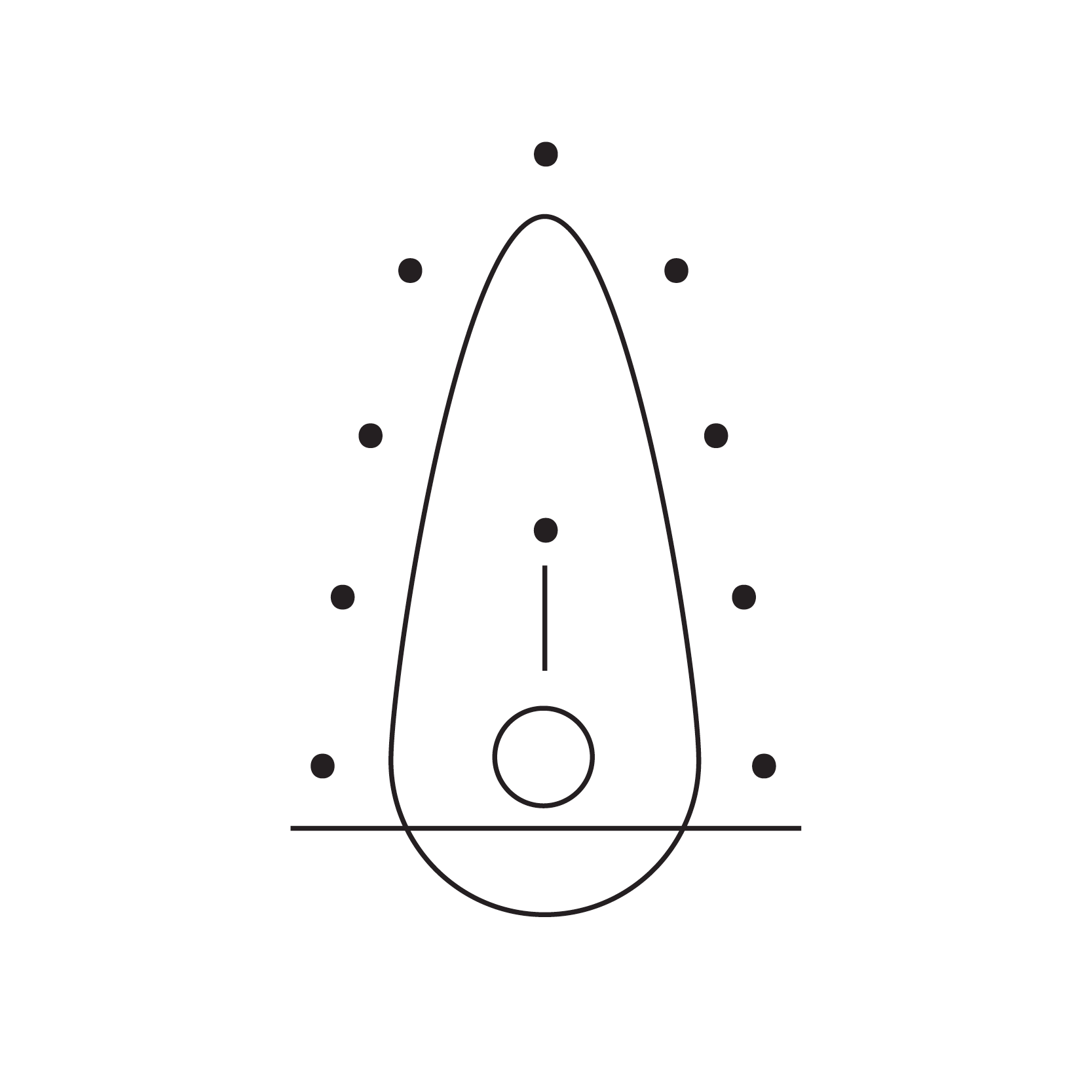

Qi, chi or prana is variously described as the lifeforce or energy in our body. In the TCM tradition our qi travels around the body via the meridian channels. Meridian channels flow through our tissues and bones, moistening and lubricating the joints whilst providing connection between the interior and exterior of the body. Harmonious balance in the body is achieved via the strength and flow of our energy through these meridian systems. Qi can be described as deficient, stagnant and when in balance stable in strength and smoothly mobile.

Meridians are organised in complementary pairs, one yin and one yang.

Kidneys (yin) & urinary bladder (yang)

Liver (yin) & gall bladder (yang)

Spleen (yin) & stomach (yang)

Lungs (yin) & large intestine (yang)

Heart (yin) & small intestine (yang)

Each meridian pairing holds specific qualities being elements, colours, seasons, taste, emotions and chakra relationships.

Our yin shapes are designed to effect the different meridians by working to bring their various characteristics and qualities into our preferred state of strong and smoothly mobile balance.

Now we have the ‘geeky’ body stuff out of the way, lets dive into the juicy mind stuff!

There are three major principles we follow in our yin practice, appropriate depth, becoming still and soft and holding for time. Sounds simple right?

Yin challenges us to be able to sit with ourselves when we are in discomfort and to not ‘run away’. For example, in my own practice, I find it much easier to ‘hide’ in a strong vinyasa class where I am focused on moving through a sequence. In yin, there is nowhere to hide and the insights and lessons that this provides me are invaluable both on and off my mat. Let’s examine these concepts in turn.

In yin yoga our appropriate depth is found when we move into a shape and encounter resistance or an edge. This can feel like a tightening, or the first point of resistance in the body where we find ‘inevitable discomfort’ without ‘risky pain’. The term ‘risky pain’ is characterised as any intense, sharp, shooting, localised pain which is not appropriate to hold. Once we have found our appropriate resistance or edge, yin asks us to be still and soft. This process of stillness and softness without the use of muscles, allows the body to naturally relax and soften into the edge we have found. As we hold yin shapes for a period of time, the body naturally extends beyond the first edge into a space appropriate for our body in that moment of time. Sounds lovely doesn’t it! Unfortunately, inevitable discomfort is just that, discomfort! And what does the brain do when we encounter discomfort? That’s right, ‘run Forest, run!’. Engage mindfulness!

As we are still and soft, we have the opportunity to practice mindfulness; of breath, of body, of feelings, of mind and of space.

Different shapes and their associated meridians evoke different emotions and it can be quite natural to feel fear, anger, anxiety, sadness and a whole host of emotional responses to our request of our body to sit in discomfort. Our breath becomes a tool, an anchor if you will, that keeps us present in our body and allows us to move through the discomfort we experience. Mindfulness of body allows an exploration of sensations both at the subtle and gross level, is what we are experiencing pleasant or unpleasant, how does our breath respond to that?

Mindfulness of feelings brings awareness to the urges within the body, an observation of sensations and the emotional flavours they evoke. Next we layer mindfulness of the mind, can we hold a mirror to the mind and become the observer? Can we differentiate between a thought and following that thought into the habit of thinking? Can we find the space between our thoughts?

Finally, we bring mindfulness to our space, do we allow ourselves to be distracted by the rustling of others, a noise from outside or can we remain focused, calm and still in awareness? Our mind is like a toddler in the supermarket when faced with distraction, can we observe without reaction?

All of these practices are as invaluable on my mat as when I step off it. A yin practice gives me tools to deal with challenging situations and know that whilst they may be challenging in the moment, they will pass and my ability to observe my thoughts before a reaction, creates a space and awareness to be much more peaceful and measured in my dealings with the challenges life inevitably throws at me. It allows a state change from our predominate state of the sympathetic nervous system of ‘fight, flight or freeze’ to our deeply restorative parasympathetic state of ‘rest & digest’ where our body is able to digest our food, mount immune responses as required and repair our body. It also has wonderful effect on our flexibility physically, mentally and emotionally making us more resilient, non-judgmental and receptive to the present moment.